The Monroe Doctrine stands as one of the most consequential policy declarations in the history of international relations. Proclaimed in 1823 by United States President James Monroe, the doctrine articulated a bold vision of hemispheric sovereignty and non-intervention that would come to shape U.S. foreign policy for nearly two centuries. Although initially conceived as a defensive statement aimed at deterring European colonial ambitions in the Western Hemisphere, the Monroe Doctrine evolved into a powerful ideological and strategic framework used to justify American political, economic, and military involvement across Latin America and the Caribbean.

Historical context

To understand the Monroe Doctrine, it is essential to situate it within the geopolitical realities of the early 1800s. The aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) left Europe politically reconfigured and economically strained. Several European powers – most notably Spain, Portugal, France, and Britain – were grappling with internal instability while simultaneously reassessing their overseas empires.

At the same time, the Americas were undergoing profound political transformation. Between 1810 and 1822, much of Latin America fought for and secured independence from Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule. Newly sovereign states such as Mexico, Colombia, Chile, and Argentina emerged, though their political systems remained fragile. The United States, itself a former colony that had gained independence less than five decades earlier, watched these developments with both ideological sympathy and strategic concern.

There was widespread fear in Washington that European powers, particularly members of the Holy Alliance – Russia, Austria, and Prussia – might intervene to restore colonial control in the Americas. Russia had also asserted territorial claims along the Pacific Northwest, further heightening American anxieties. Against this backdrop, U.S. policymakers began to contemplate a formal declaration that would define the Western Hemisphere as a sphere free from European interference.

Intellectual and philosophical foundations

The Monroe Doctrine did not emerge in isolation; it was deeply rooted in Enlightenment thought and the early American political tradition. Core principles such as national sovereignty, self-determination, and republican governance informed its underlying logic. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, both former presidents, played an influential advisory role in shaping Monroe’s thinking. Jefferson, in particular, believed that the Americas should be governed by principles distinct from those of monarchical Europe.

He envisioned a hemisphere of republics bound by shared political values rather than imperial domination. Another critical influence was American exceptionalism – the belief that the United States occupied a unique moral and political position in world history. This idea suggested not only that the U.S. had a right to protect its democratic experiment, but also that it bore a responsibility to prevent Old World powers from undermining republicanism in the New World.

Importantly, the doctrine also reflected pragmatic considerations. The United States lacked the military capacity in 1823 to enforce a sweeping hemispheric policy on its own. British naval power, driven by Britain’s interest in maintaining open markets in Latin America, effectively supported the doctrine’s enforcement, even though Britain was not formally named as an ally.

Core principles of The Monroe Doctrine

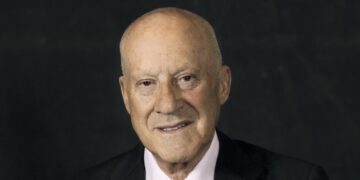

President James Monroe articulated the doctrine during his annual message to Congress on December 2, 1823. While the speech addressed numerous domestic and foreign policy matters, several key passages laid the foundation for what would later be termed the Monroe Doctrine. Its central principles can be summarized as follows:

a. Non-colonization

Monroe declared that the American continents were no longer open to future colonization by European powers. This statement was revolutionary in its time, effectively challenging centuries of imperial practice and asserting that the political fate of the Western Hemisphere lay outside European jurisdiction.

b. Non-intervention

The doctrine warned European nations against interfering in the affairs of independent states in the Americas. Any attempt to extend European political systems into the Western Hemisphere would be viewed as a threat to U.S. peace and security.

c. Separation of spheres

Monroe emphasized a clear distinction between the political systems of Europe and the Americas. While the United States pledged not to interfere in existing European colonies or internal European affairs, it expected reciprocal restraint in the Western Hemisphere.

d. Neutrality in European conflicts

The doctrine reaffirmed America’s commitment to neutrality in European wars, provided that U.S. interests were not directly threatened. This stance reflected a continuation of George Washington’s earlier warnings against entangling alliances.

Immediate reception and early impact

In the immediate aftermath of its announcement, the Monroe Doctrine generated limited international reaction. European powers, preoccupied with their own postwar challenges, largely dismissed the statement as aspirational rhetoric from a relatively weak nation. However, Britain’s tacit support proved decisive. The Royal Navy, as the dominant maritime force of the era, effectively deterred other European states from challenging the doctrine. Within the United States, the doctrine was initially met with cautious approval rather than widespread acclaim. It did not become a central pillar of foreign policy overnight. Instead, its significance grew gradually as successive administrations invoked and reinterpreted it in response to new geopolitical realities.

Expansion and reinterpretation in the nineteenth century

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Monroe Doctrine evolved from a defensive declaration into a more assertive policy instrument. As the United States expanded territorially and economically, its leaders increasingly viewed the Western Hemisphere as a natural sphere of influence.

a. Manifest Destiny and hemispheric ambitions

The doctrine’s expansion coincided with the rise of Manifest Destiny – the belief that the United States was divinely ordained to expand across North America. While Manifest Destiny primarily focused on continental expansion, it reinforced the idea that American political and cultural values should dominate the hemisphere. U.S. actions such as the annexation of Texas, the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), and increased involvement in Central America reflected a growing willingness to assert regional dominance, often under the implicit logic of the Monroe Doctrine.

b. The Clayton-Bulwer treaty and European relations

The doctrine also influenced diplomatic negotiations with European powers. The Clayton-Bulwer Treaty of 1850, for example, reflected U.S. efforts to prevent exclusive European control over potential interoceanic canals in Central America, anticipating future strategic and commercial interests.

The Roosevelt Corollary

One of the most significant reinterpretations of the Monroe Doctrine occurred in 1904 under President Theodore Roosevelt. Known as the Roosevelt Corollary, this policy asserted that the United States had the right to intervene in Latin American countries to maintain stability and prevent European intervention. Roosevelt argued that chronic wrongdoing or financial instability in the Western Hemisphere could invite European involvement, thereby justifying preemptive U.S. action. In effect, the corollary transformed the Monroe Doctrine from a shield against external interference into a sword of regional intervention.

Practical consequences

The Roosevelt Corollary led to numerous U.S. interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean, including in the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Haiti, and Cuba. While these actions were often justified as necessary to maintain order and sovereignty, they also generated deep resentment and accusations of imperialism.

The Monroe Doctrine in the Cold War era

During the twentieth century, the Monroe Doctrine acquired renewed significance in the context of the Cold War. The ideological struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union reframed hemispheric security concerns.

a. Anti-communism and containment

U.S. policymakers invoked the doctrine to justify opposition to communist movements and governments in the Americas. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 stands as the most dramatic example, when the United States confronted the Soviet Union over the placement of nuclear missiles in Cuba, citing the principle that external powers should not establish military footholds in the hemisphere.

b. Intervention and controversy

Cold War applications of the doctrine included support for coups, military regimes, and counterinsurgency efforts in countries such as Guatemala, Chile, and El Salvador. While framed as measures to protect regional security, these actions often undermined democratic institutions and human rights, fueling long-term instability and mistrust.

Criticisms and controversies

The Monroe Doctrine has been the subject of sustained criticism, particularly from Latin American scholars and political leaders. Key critiques include:

a. Accusations of imperialism

Many argue that the doctrine served as a justification for U.S. imperialism rather than genuine hemispheric solidarity. By positioning itself as the arbiter of regional stability, the United States often marginalized the sovereignty of smaller nations.

b. Double standards

Critics also highlight the doctrine’s selective application. While opposing European intervention, the United States frequently intervened unilaterally, creating a double standard that undermined its moral authority.

c. Legal and ethical concerns

From an international law perspective, the doctrine lacks formal legal standing. It represents a unilateral policy rather than a mutually agreed framework, raising questions about its legitimacy in a rules-based global order.

The doctrine in the post-Cold War world

In the twenty-first century, the Monroe Doctrine occupies an ambiguous position. Globalization, the rise of new powers, and evolving norms of sovereignty have challenged traditional hemispheric frameworks. Some U.S. leaders have declared the doctrine obsolete, emphasizing partnership and multilateralism. Others have reaffirmed its relevance, particularly in response to increased involvement by external powers such as China and Russia in Latin America. Modern interpretations tend to focus less on military intervention and more on economic influence, diplomatic engagement, and strategic competition, reflecting changing tools of global power.

The Monroe Doctrine in the era of Donald Trump

During Donald Trump’s presidency, the Monroe Doctrine re-emerged as a clear guiding principle of U.S. policy toward the Western Hemisphere. Unlike earlier administrations that treated the doctrine mainly as a historical reference, Trump’s leadership approached it as a living framework for protecting American strategic interests. Latin America was viewed as a critical geopolitical space where U.S. influence needed to be actively defended against external powers seeking to expand their presence.

A central feature of this approach was the strong opposition to foreign involvement in the region by countries such as China and Russia. Their growing economic, technological, and military engagements in Latin America were interpreted as modern forms of intrusion rather than normal commercial relations. Under Trump, the Monroe Doctrine was effectively updated to address influence gained through loans, infrastructure projects, energy investments, arms sales, and digital networks, rather than through traditional colonial control.

Venezuela became the most visible example of how this doctrine was applied in practice. The administration argued that the country’s close ties with Russia, China, and Cuba posed a threat to hemispheric stability. In response, the United States imposed broad economic sanctions, challenged the legitimacy of the existing government, issued strong warnings against deeper foreign involvement, and eventually using military intervention to capture and oust Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

These measures reflected an assertive interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine aimed at limiting external influence in the Americas. Throughout Trump’s presidency, U.S. policy in the region relied heavily on economic pressure, diplomatic isolation, and strategic signaling. Multilateral institutions played a secondary role, as the administration favored direct engagement and unilateral decision-making. This reinforced the perception of the Monroe Doctrine as a U.S.-driven principle rather than a shared hemispheric agreement.

At the same time, the application of the doctrine under Trump showed a shift away from judging internal political systems toward focusing on external alignments. The primary concern was not how governments were structured domestically, but whether they allowed non-hemispheric powers to gain lasting strategic footholds. In this sense, Trump’s presidency reflected a return to the original logic of the Monroe Doctrine: preventing outside interference rather than reshaping internal governance.

Overall, Donald Trump’s presidency demonstrated that the Monroe Doctrine remains a flexible and influential tool of U.S. foreign policy. By adapting its principles to modern forms of power and competition, his administration reaffirmed the doctrine’s relevance in an era defined by global rivalry, economic leverage, and strategic influence rather than formal empire-building.

Enduring legacy and global significance

The Monroe Doctrine’s enduring legacy lies in its profound influence on how the United States understands its role in the world. It established a precedent for linking regional stability to national security and for asserting ideological boundaries in international politics. Beyond the Americas, the doctrine contributed to broader debates about spheres of influence, intervention, and the balance between sovereignty and security. Its principles have been echoed, adapted, and contested in various global contexts, underscoring its lasting relevance.

Conclusion

The Monroe Doctrine is far more than a historical artifact; it is a living framework that has shaped nearly two centuries of American foreign policy. From its origins as a defensive warning to its evolution into a justification for intervention, the doctrine reflects the changing ambitions, anxieties, and values of the United States. Understanding the Monroe Doctrine requires grappling with its dual nature – as both a protector of independence and a vehicle for dominance.

Its history offers critical insights into the complexities of power, principle, and responsibility in international relations. As global dynamics continue to evolve, the lessons of the Monroe Doctrine remain instructive, reminding policymakers and scholars alike that declarations of principle can carry consequences far beyond their original intent.