The “madman theory” is a political strategy that gained prominence during the Cold War era, most notably associated with U.S. President Richard Nixon. It is rooted in the calculated projection of irrationality or unpredictability by a leader to influence the behavior of adversaries, often in diplomatic or military contexts. The basic premise is simple but profound: if an opponent believes a leader is unpredictable or even capable of irrational acts – particularly with access to military or nuclear power – they may be more inclined to back down or make concessions to avoid provoking a potentially catastrophic response.

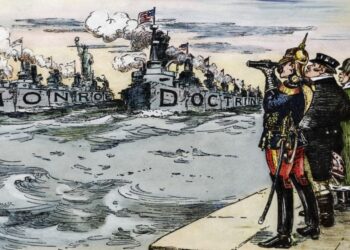

Although the concept was famously adopted by Nixon, the roots of the madman theory can be traced through history and political theory, finding parallels in deterrence strategies, psychological warfare, and game theory. In modern politics, it remains a controversial but relevant concept, sometimes implicitly deployed by various leaders around the world.

Origins and theoretical foundations

The madman theory, while popularized in the 20th century, has antecedents in earlier political and military thought. The strategic use of feigned madness appears in ancient texts such as Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, where unpredictability is emphasized as a tactical advantage. Shakespeare’s Hamlet famously pretends to be mad to obscure his true intentions and gain leverage over others.

In modern political theory, the madman approach intersects with game theory and deterrence theory, especially in the context of nuclear brinkmanship. In a game-theoretic framework, irrationality can be a powerful signal. For example, if a player in a high-stakes game credibly signals that they might not act in their own rational best interest, their unpredictability can force the other party to avoid escalation.

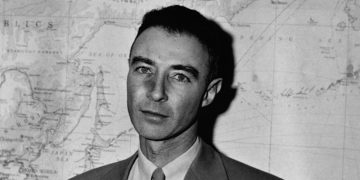

During the Cold War, nuclear deterrence was underpinned by the logic of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), which required that both sides believe that any nuclear attack would result in total annihilation. The madman theory took this one step further, suggesting that if a leader appeared unstable enough to actually initiate such destruction, even irrationally, it might deter adversaries more effectively.

Nixon and the madman theory

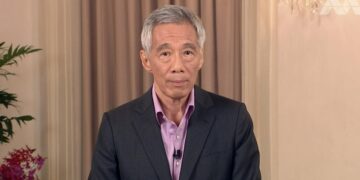

Richard Nixon is the most well-known practitioner of the madman theory. During his presidency (1969-1974), Nixon and his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger developed a strategy that involved projecting an image of the president as volatile and potentially unhinged. Nixon hoped that the Soviet Union and North Vietnam would believe that he was capable of extreme and unpredictable actions, including the use of nuclear weapons, if provoked.

One of the most illustrative examples of this theory in practice was the “madman” nuclear alert of 1969. In October of that year, Nixon ordered a global military alert, involving increased nuclear readiness, with the intention of signaling to the Soviet Union and North Vietnam that he was capable of taking drastic actions to end the Vietnam War. The idea was that this demonstration of potential irrationality would create fear and push adversaries toward negotiation.

However, the effectiveness of Nixon’s approach is debated. While some argue that it contributed to eventual peace talks, others point out that adversaries often did not believe the bluff or saw through the strategic posturing. Additionally, the strategy risked severe escalation, as feigned madness can be misinterpreted, leading to unintended conflict.

Mechanics of the madman theory

The madman theory operates through several key mechanisms:

a. Perception management

Central to the theory is the careful crafting of a public image that suggests instability or irrationality. This may involve erratic behavior, contradictory statements, or the deliberate leakage of alarming information. The aim is to make adversaries believe that pushing the leader too far could trigger an unpredictable and possibly catastrophic reaction.

b Strategic ambiguity

By refusing to clarify intentions or red lines, a leader employing the madman theory keeps adversaries guessing. This ambiguity can heighten anxiety and caution in others, especially when nuclear or military options are perceived to be on the table.

c. Deterrence through fear

The primary objective is deterrence. If opponents fear that a leader might act irrationally – launching an attack or breaking diplomatic norms – they may avoid provocations or be more amenable to compromise.

d. Backchannel signaling

Often, the madness is not projected uniformly to all audiences. Diplomatic backchannels are used to reinforce the image of volatility to adversaries while maintaining more rational communication with allies or domestic audiences.

Applications beyond Nixon

Though Nixon’s use of the madman theory is the most documented, other leaders have employed similar tactics, either intentionally or through naturally erratic behavior.

a. Kim Jong-un (North Korea)

The North Korean regime has long utilized unpredictability as a form of political leverage. Frequent missile tests, abrupt diplomatic shifts, and aggressive rhetoric are part of a broader strategy to maintain strategic ambiguity and deter foreign intervention.

b. Donald Trump (United States)

Many analysts have argued that Trump, whether deliberately or instinctively, embodied aspects of the madman theory. His unpredictable foreign policy decisions – such as sudden troop withdrawals, threats against adversaries on social media , and unconventional summits – led both allies and adversaries to treat his intentions with caution.

c. Vladimir Putin (Russia)

Putin’s approach to geopolitics often includes elements of unpredictability and strategic ambiguity. The annexation of Crimea in 2014, cyber operations, and veiled nuclear threats during the Ukraine conflict have all contributed to a sense of calculated irrationality that keeps NATO and other actors cautious.

Criticism and risks of the madman theory

While the madman theory has theoretical appeal, it is also subject to extensive criticism:

a. Unpredictability is a double-edged sword

While adversaries might be deterred, allies may also become anxious or disillusioned. Unpredictable behavior can undermine alliances, weaken international cooperation, and reduce the credibility of a leader’s commitments.

b. Escalation risk

A central danger is that perceived irrationality can lead to miscalculations. If adversaries believe a leader might act irrationally, they may act preemptively or misread intentions, leading to unnecessary conflict.

c. Domestic repercussions

Leaders projecting madness risk losing legitimacy or support at home. Populations generally prefer stable and rational leadership, especially in democratic systems. Feigned madness can be indistinguishable from actual incompetence or instability.

d. Moral and ethical questions

Intentionally deceiving others about one’s mental state raises ethical concerns, particularly when nuclear weapons are involved. Is it justifiable to manipulate perceptions at the risk of global security?

Contemporary relevance

In an era marked by great power competition, populist leaders, and rapid information dissemination, the madman theory remains relevant – though perhaps more dangerous. Social media and 24-hour news cycles amplify erratic behavior, making it harder to distinguish between deliberate strategy and genuine instability.

The international system is also more interconnected today. Unpredictable actions can have cascading effects across financial markets, alliances, and global security. Furthermore, with nuclear proliferation and cyber warfare in the mix, the costs of miscalculation are higher than ever.

Conclusion

The madman theory of politics is a high-stakes strategy rooted in psychological manipulation and strategic unpredictability. While it can be an effective deterrent under certain conditions, it also carries significant risks – both for the leader who employs it and for the international system at large.

As global politics continue to evolve, understanding the dynamics and consequences of this theory is crucial. Whether used intentionally or as a byproduct of personality, the perception of irrationality in leadership remains a powerful force – one that can shape wars, negotiations, and the fate of nations. The real challenge lies in discerning when the madness is calculated, and when it is all too real.