When a company is formed, the founders typically retain a law firm to advise them in connection with setting up the company. Most law firms that advise founders will require that they sign an engagement letter acknowledging that the company and not they are the client. This means simply that the founders do not have legal counsel that are protecting their individual interests. Founders typically conclude that there is no need for separate representation because, as the sole stockholders and directors, they essentially “are” the company, and what is good for the company is therefore good for them.

While this is true for many purposes, it is not true in all situations. Moreover, as the company grows and adds employee and investor stockholders, founders often lose voting control of the company and blend into the broader class of common stockholders. At the same time, the issues that affect the founders as common stockholders become increasingly complicated.

While in some situations the founder will be told by company counsel to retain separate counsel, it is not company counsel’s obligation to do so unless a conflict exists. In addition, even when the founders may decide to rely on company counsel, this only works well when all founders are privy to the same conversations with company counsel, a dynamic that rarely exists in practice.

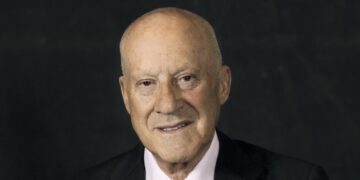

This article describes a number of key legal issues that founders often confront in forming and building a company, and describes those situations in which separate legal counsel may be able to assist them in bringing about a more favorable result. In these cases and others that might arise, founders should seriously consider retaining separate counsel to advise them either individually or along with the larger group of common stockholders.

1. Agreements with prior employers

Often one or more founders were previously employed by a company with which they had a non-competition and/or assignment of inventions agreement. Issues may exist as to whether the intellectual property that the founders intend to build the new company around is free and clear of any claims a prior employer might have pursuant to an assignment of rights agreement, or whether starting and operating the new company would constitute a breach of a prior non-compete agreement.

Clearing up such issues relating to prior employers is best addressed prior to leaving a job to start a new company. Often the momentum to start a new company builds to the point that it can be difficult to turn back even in the face of a possible breach of contract claim, or worse, an allegation that a founder has stolen trade secrets or other intellectual property rights.

Prospective co-founders that do not have such constraints, and who are vested in seeing the new venture launch, have less at stake if a breach or other violation were to be alleged in the future, and therefore may be more inclined to push a co-founder to take such a risk. Any founder that has questions about rights and restrictions relative to a prior employer should consider seeking advice of counsel to fully understand the implications of this risk.

Unlike other situations described below, this is a situation in which legal counsel for the prospective company should be able to represent the founder’s interests as well as the new company because their interests are aligned. However, it is critically important that company counsel be made aware of all the relevant facts, and that any founder that has risks related to prior employment be directly involved in discussions with company counsel.

2. Contributions of intellectual property

In a tech startup, intellectual property that has been developed by one or more founders will generally be contributed to the company in exchange for founders stock. Once the intellectual property is contributed, it becomes the property of the company and the contributing founder no longer has any personal rights in it. As a result, the contributing founder may want to consider;

- Delaying the contribution of the intellectual property as late in the formation process as possible so as not give up rights prematurely.

- Structuring the contribution of intellectual property so that it reverts in certain situations, such as in the event the founder is terminated without cause or is divested of his or her stock, or in the event the company fails to move forward for any reason such as the failure to secure financing by a certain date.

In addition, in some instances, the founder contributing the intellectual property may be the inventor of other intellectual property that he or she does not intend to contribute to the company. The contribution agreement should be carefully drafted and reviewed by counsel with this in mind so as to not unwittingly sweep in intellectual property that is not intended to be the property of the new company.

In addition, all employees, including founders, are typically required to assign to the company all rights in work product, including all intellectual property they develop relating to their employer’s business or based on company intellectual property, during their employment. For a founder that may continue to pursue innovation in his or her field, a broad assignment of rights agreement may result in the contribution to the company of technology that they develop on their own time and with their own resources, and which may not be directly related to the work of the new company.

This can be particularly applicable to academics or industry luminaries who may be pioneers in a given field. Founders should carefully consult with legal counsel to ensure that the scope of the ongoing assignment of rights agreement is reasonable in light of any ongoing work they may be doing on the side. The timing and scope of the assignment of rights is an area in which the interests of the company are likely not to be aligned with that of the individual founder. Founders should consider retaining separate legal counsel to advise them on these issues.

3. Founder’s stock

To ensure that stock issued to founders is properly “earned” by each founding stockholder, startup companies typically put in place stock restriction agreements with each founder. The primary purpose of this agreement is to give the company a right to purchase shares held by a founder in the event that the founder leaves the company for any reason. This purchase option generally applies only to shares that are unvested at any given point in time, with shares becoming vested over a predetermined, usually time-based, schedule.

There are several variables that need to be determined when putting in place stock restriction agreements. They include the overall duration of vesting, whether there is any up front vesting, what period of time, if any, must elapse before there is any additional vesting, and under what circumstances there may be additional or accelerated vesting-for example in connection with a change of control of the company, or upon the termination of the founder. Venture capitalists have established certain acceptable ranges for these variables.

From the founders’ perspective, one of the most important areas of concern is the basis upon which their shares accelerate in the event they are terminated. In the event the founder resigns voluntarily or is terminated for cause, no additional stock vests. However, if the founder is terminated without cause, or resigns for good reason (in other words, is “forced out”), there arguably should be some compensation to the founder out of fairness, and to deter the board from terminating key people in order to recoup equity.

Occasionally founders are able to negotiate for partial or even full acceleration. The definition of what constitutes “cause” for purposes of determining whether termination triggers acceleration is critical but subtle, and any common stockholder should be aware of the drafting options and seek advice of counsel to ensure his or her interests are protected. Related to the question of whether acceleration occurs upon termination is the issue of what happens upon a change of control.

Full acceleration is often a reasonable starting point for negotiation. After all, if the company is sold, the founders who are still with the company likely made significant contributions to put the company in a position to be acquired. Venture capitalists and other stockholders who do not stand to realize any acceleration, however, are likely to oppose acceleration upon change of control.

Full acceleration will simply result in dilution to them and reduce their share of the consideration received in the acquisition. If full acceleration cannot be negotiated, an alternative is to request additional and possibly full acceleration if the founder is let go or resigns for good reason within one year following a change of control-a mechanism that is sometimes called “double trigger” acceleration.

However, this compromise position only works well in practice when the change of control calls for the founders to receive “replacement” equity with respect to their unvested stock. The “double trigger” concept does not translate as cleanly where the consideration received by the selling stockholders is cash, and specific provision should be made for this situation, again with advice of counsel.

If full acceleration either at change of control or pursuant to a double trigger is not acceptable, then the company and the founder may agree to a mechanism that is simpler to apply, such as one year or 50% vesting upon a change of control. Founder’s stock issues, especially as they relate to vesting, can be quite complex and assistance of legal counsel can help improve a founder’s situation significantly. Founders should consider retaining separate legal counsel to advise them on these issues.

4. Minority shareholder protections

While the founders in most startups enjoy a high degree of mutual trust and camaraderie, their relationships can change and become strained over time. Any founder who is a minority stockholder is at risk of being terminated at any time by the board of directors. Depending on whether the founders have put in place stock restriction agreements, as discussed above, a minority stockholder could be terminated and be completely divested of his or her equity position as well.

This would seem to be a particularly inequitable outcome if the terminated stockholder had previously contributed either cash or some other asset, such as core intellectual property, that is critical to getting the company launched and that may even serve as the cornerstone of the new company’s business plan.

Founders should understand basic corporate governance issues at the time of formation so that they are not unpleasantly surprised if an issue arises that may result in their separation from the new company. If a founder is concerned about the possibility of being oppressed by majority stockholders, consideration should be given to incorporating the company in a city/region/county/state where the local law affords minority stockholders greater protections.

Sophisticated company counsel should be able to provide the legal framework necessary for founders to understand how they may be affected by decisions regarding corporate governance and fiduciary duty issues. Nonetheless, an in-depth discussion on these issues is outside the scope of what company counsel would typically be expected to do, and any founder that is sensitive to concerns in this area should consider retaining separate counsel to focus more deliberately on these considerations.

5. Non-comete agreements

Founders are typically asked to sign a non-competition agreement with the company, if not at the time of formation, then certainly at the time it becomes funded by outside investors. The terms of the non-competition agreement can have a chilling affect on the founder’s ability to pursue gainful employment after leaving the company.

For example, most non-competition agreements prohibit the employee from working in the same field for a period of time after leaving the company, regardless of the reason for departure, which could include termination without cause in connection with the bankruptcy of the company or as a result of a major reduction in force unrelated to performance.

Well-informed employees might seek to get the non-compete to terminate in the event that they are terminated without cause, or in the event the company goes into bankruptcy. Alternatively, an employee may seek some severance payment for a period of time that runs concurrently with the non-compete so that they do not bear the full economic burden that a restrictive non-compete poses.

The scope of non-compete agreements is certainly an area in which the company’s interests and those of the founders are not aligned. The company’s interest is for the non-compete to be broad, while the employee would prefer that it be narrow so as not to restrict them upon their separation from the company.

The key to negotiating a fair non-competition agreement is to engage counsel prior to accepting the offer so as to better understand what the areas of concern should be and what alternative proposals might enable the founder and the company to strike a balanced deal that addresses the legitimate business interests of the company without unduly burdening the employee.

6. The venture capital transaction

Several issues arise in the context of venture capital financings in which the interests of the founders are not necessarily aligned with the interests of the company. For example, founders may be asked to give broad representations and warranties in their individual capacities as part of early rounds of financing. The company and its legal counsel may have no reason to object to such representations on behalf of the founder. But the founders may not be comfortable offering up some or all of the requested representations and warranties.

In addition, the terms of a venture financing have a direct impact on the future returns that the founder stockholders can realistically expect to achieve on their founder stock. For example, venture capital firms often require a liquidation preference equal to their original investment (or even a multiple of this investment) plus some accruing dividend. This liquidation preference gets paid before any proceeds get paid out to the founders who are common stockholders.

In a company that has raised tens of millions of money, common stockholders may not realize any return on their stock unless the company eventually goes public. Moreover, when a company needs to raise funding in a situation in which it has failed to achieve important milestones, the financing terms can be punishing to both the founders and the earlier stage investors. In such a situation common stockholders often have their equity positions “washed out” by subsequent investors.

For these reasons, founders are advised to fully understand the impact that a prospective financing will have on them personally as common stockholders. Before a company commits to a transaction that has this impact on the founders’ interests, the founders should consider what leverage they have in the negotiation to improve their post-funding position, and be informed as to what protections they might seek in the transaction.

Founders may in fact have a sufficient number of shares that their vote is required to close a subsequent round of financing. This is very likely for those companies that have only been through one round of venture financing. Founders at this stage can use this vote to influence the structure of a financing by threat of veto if they are concerned that the transaction stands to have an onerous impact on the holdings of the common stockholders, and the likelihood that they will some day participate to any significant degree in a liquidity event.

Alternatively, common stockholders may use their collective leverage as the management of the company to affect the structuring of a transaction. By exercising their leverage, the founders may be able to negotiate for the right to participate in the liquidation preference at some higher level, thereby leaving them with a more realistic opportunity to achieve liquidity.

Alternatively they might negotiate for a management bonus pool that entitles them to a contractual right of payment in the event that the company has a liquidity event. The important point is that founders often have a legitimate reason to be concerned about the impact of a financing, and that they probably do, in most cases, have more leverage than they realize. The key is to raise the concern and exercise the leverage early in the negotiation process.

7. Stay incentives

In venture-backed companies, founders are often members of the executive team and critical to the growth and success of the company, and to the company’s ability to execute on important strategic initiatives such as a financing or sale of the company. In connection with either a significant down round financing or a change of control, certain key executives may begin to question whether it is in their best interests to remain with the company through such an event.

Founders in this position might consider approaching the president or board of directors to request an incentive to keep them motivated through the closing of the transaction or some later date. Bonus arrangements, often referred to as “stay bonuses”, are one vehicle for accomplishing this objective. Another might be to provide a severance package that would give the concerned employee/founder a cash payment in the event he or she is let go following the financing or change of control.

A third mechanism would be to provide for additional stock vesting upon the occurrence of the transaction. Most stay packages incorporate elements of cash and stock incentives. While having such an incentive in place may be in the best interest of the company and employee/founder alike, it may well be that the company does not recognize the issue or recognizes the issue but has decided not to be proactive in addressing it.

As such, it may be incumbent upon the affected executives to protect their own interests by approaching the company with a proposal. While working through such stay incentives can often be done with the assistance of company counsel, founders should consider consulting with their own legal counsel as to the options available and the pros and cons of each.

8. Acquisition methods

Acquisitions are often rife with issues that have a direct impact on the founders both as members of the broader group of common stockholders, and as prospective employees at the buyer company. For example, many employee incentive plans provide that the board of directors of a company can decide at the time of an acquisition whether to accelerate unvested stock options or restricted stock grants.

Accelerating such grants would allow the employees to hold a greater number of shares at the time of the acquisition, and thereby result in more of the proceeds being paid out to the employee stockholders. Another consideration that arises in acquisitions is the extent to which the founders and other common stockholders will be required to indemnify the buyer company in the event that certain representations made by the target company in connection with the acquisition agreement turn out to be false resulting in damages to the buyer.

As a final example, for those founders who will be offered employment with the buyer, a whole range of issues arise around the terms of employment going forward, including salary, equity and the scope of a new non-compete. In all three of the cases described above, the company’s interests are not aligned with the interests of the founders and separate legal counsel is advisable. With advice of counsel a well coordinated founder group may have the opportunity to interject itself into the negotiation process early, improving the outcome for the founders and other common stockholders alike.

Summary

While it is very common for founders to rely on the advice of company counsel at the outset of the formation of the company, there are certain situations that might suggest that founders should have separate counsel to protect their own interests. As a company grows and takes on outside investment, the interests of the founders diverge. Company counsel will inform any founder who raises an issue that may be contrary to the interests of the company that it represents the company, not the founder’s interests, and that the founder should seek separate counsel.

A founder should seriously consider engaging separate counsel at the time of the formation of the company to deal with a number of issues that are determined around the time of formation. Having legal counsel “on retainer” can then be helpful to a founder at future points in the life stage of the company. Counsel can then point out to the founder when representation is necessary or advisable situations that might not be apparent to other than the most sophisticated founder.